The Roth 401k - Possibly Life’s Biggest Financial Decision

Almost every employer currently offers the option of saving into their 401k as an after-tax Roth instead of pre-tax. It’s been a developing change, and most people aren’t aware. Although this could be the single biggest financial decision of one’s life.

The paradigm shift.

I entered the financial planning business in the mid-90s, at a time when employers were migrating away from pensions and asking employees to be responsible for their own retirement savings via 401k and 403b plans. Owning investments was foreign to most Americans, and an incentive was necessary for this shift to work. The carrot was pre-tax savings. By investing $10,000 into a pre-tax retirement plan, you could reduce your income by $10,000, and avoid paying taxes on that deposit. For someone in the 28% Federal bracket, that came to a federal tax reduction of almost $3,000.

The extra $3,000 was realized in their paychecks or during tax time. We’d tell people to take that savings and invest it into something else, like a college plan, brokerage account or a Roth IRA. But most people would simply spend it.

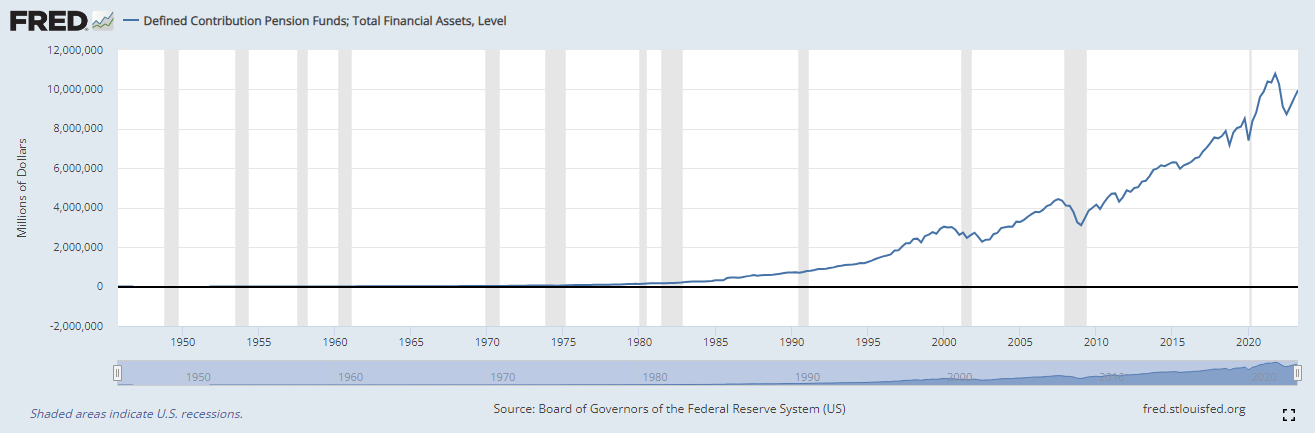

This graph only represents a portion of the total defined contribution plan balances. But it illustrates the dramatic shift into their use.

Fast forward 30 years, 401k and 403b plans have become mainstream, with individuals having hundreds of thousands and even millions of dollars invested. Almost like clockwork, the more people saved into their plans the more money they have today. Awesome. Except for one big problem. All that money they accumulated will be taxed as income when they spend it.

Most people I speak with assume their tax rates will be lower in the future, but that might not be the case. Either way, the more years a Roth has time to grow, the less relevant future tax rates are in determining the benefit. While at the same time, higher tax rates in the future would further benefit the Roth saver.

Why taxes might be higher in the future.

Tax rates are a balancing act between covering the governments budget, and not over charging citizens/corporations, or they won’t spend and grow our economy. We currently have the lowest tax rates since around the Great Depression (1930s).

Since the financial crisis of 2008, excessive government borrowing and Federal Reserve infusions have fueled our economic system. Extremely low interest rates tipped the balance toward charging citizens/corporations very little and put the focus on growing the economy. The government borrowed excessively to make up for their revenue shortfalls.

We have created trillion-dollar imbalance problems (our debt exceeds our economy). Trillion-dollar problems don’t fix themselves in months. It takes many years, maybe decades. In the meantime, the problem intensifies as our federal debt continues to grow. The only way to reduce the deficit is for the federal government to raise more revenue (tax) than it spends. And then apply that surplus to paying down debt, for many years thereafter.

A sustained surplus that pays down debt is not likely to happen. In my 50-year life, it’s only happened four times. What is more realistic, is to raise revenue (taxes) enough to slow the increase of debt, while making payments on the debt, and simultaneously grow the economy at a faster rate. This is an extremely tricky endeavor to say the least. To be blunt, if the government could collect enough money to cover its bills and not tank the economy, it would already have done it. What this likely means is that higher taxes could become systemic, slowly getting higher, and lasting for decades.

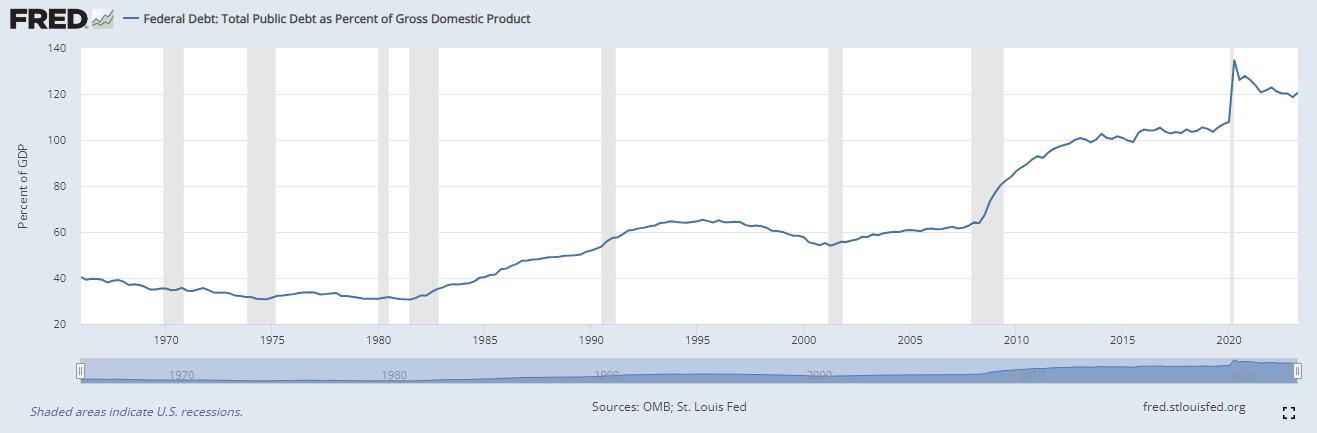

How big is the imbalance?

We have almost $31 trillion of national debt and the federal reserve balance sheet is almost $9 trillion. That equals about $40 trillion dollars. GDP (our economy) is around $25 trillion. We have never experienced that extreme dynamic of debt relative to our economy. To put it into perspective, at the end of 2007 (before the financial crisis of 2008), total public debt was around $9 trillion, and the Federal Reserve balance sheet was around $880 million. GDP at that time was almost $15 trillion.

Chart above shows federal debt to GDP. It does not include the federal reserve balance sheet assets, which have grown about 8 trillion since 2009.

We’ve pumped an unprecedented amount of money into the system (combined federal debt and Federal Reserve balance sheet) to grow our economy only a fraction of that influx. The combined federal debt and Federal Reserve balance sheet went from around 69% of GDP at the end of 2007, to 151% today. It exceeds our GDP by a whopping 14 trillion, which was what our entire GDP was back in 2007.

Why does debt to GDP matter?

The government pays its bills by taxing from the economy. Our bills include the cost of borrowing $30 trillion. If the pool of money (GDP) we have available to tax from is shrinking relative to the growing expense of the debt, then eventually there is very little the government can do to avoid default other than charging more in taxes.

What’s in your control and not in your control.

You have very little control over how the government will fix their balance sheet. But you have a tremendous amount of control over how your future income will be taxed by using Roths.

Roths don’t save you tax dollars today. They do something even better than that. They are not taxed later in life (5 years after deposit or after age 59.5 whichever is greater). Right now, the trillions of dollars that people have in pre-tax retirement accounts is 100% exposed to the problems I outlined above. Whatever income tax rates are when you spend the money is what you will have to pay. There’s very little you can do to change that scenario when the time comes. Just like solving the government problem will take many years to unfold, solving your own retirement tax problem also takes years of planning and foresight. And I believe it’s totally worth it.

The power of using a Roth.

Here’s an example to put it into perspective. I’ll use $1 million as an account size. Many people who are proactively saving amply into their retirement plans will reach that milestone, and beyond.

Two different people, Ted and Mary, each have $1 million in their retirement plan. Ted is 100% pre-tax, and Mary has 100% Roth. For simplicity’s sake, I’ll assume two different tax rate scenarios for Ted. One at 20% and one at 30%. For example, if Ted takes out $10,000 from his plan, he would either pay $2,000 in taxes or in the other scenario, he pays $3,000 in taxes.

Over the course of 40 years, I’ll assume that both accounts earn 6.5% annual return, and are completely used up. That’s an annual distribution of $66,380. At the end of 40 years both Ted and Mary’s accounts have a zero balance.

Each will take out a total of $2,655,200 during the 40 years. Under the 20% tax scenario, Ted would pay $531,040 in taxes. In the 30% scenario Ted pays $796,560 in taxes. Mary pays nothing. She gets to keep the entire $2,655,200.

There is something about Mary’s strategy that I like much better.

Step 1 - Change your workplace investing from pre-tax to Roth.

You will no longer get a current tax deduction when you stop saving pre-tax. Don’t worry about that little carrot. Instead, focus on accumulating the maximum amount of money you can in the plan as a Roth and let it grow for a decade or more. Eventually when you retire, you’ll enjoy spending that money with zero taxes. Just like Mary.

I believe most people still working should make this change from pre-tax savings to Roth. Some exceptions might apply.

Step 2 - See if your employer allows for in-service withdrawals, or Roth conversion within the plan.

If you are below the 32% tax bracket, do the math and see how much money you could convert to a Roth, staying under that bracket. If you are over the 32% bracket, then you have a more difficult decision to make. Consider converting into a Roth from your existing pre-tax retirement plan. However, this is extremely important - you will have to pay taxes on the amount you convert from your pre-tax retirement plan to a Roth. For example, if you converted $100,000 from a pre-tax plan into a Roth, it will be as if you earned an additional $100,000 of income in the year you convert. So, when you get your taxes done, you’ll need to have the money available to pay that large tax bill (which could be over $23,000 depending on your bracket).

Look at converting as buying your partner (the government) out of your business (your retirement plan). Their offer on the table is the lowest price it’s been in almost 100 years (lowest tax rates since the Great Depression era). Assuming historical market returns, the value of your business will be much greater in the future. It’s the perfect opportunity.

Step 3 - Let it grow.

The Roth advantage favors growth. Someone that invests $100,000 ($20,000 over 5 years in their 401k), and lets it grow for 30 years at 8% would accumulate $1,006,265. If they then withdraw from the $1 million over the next 40 years, and earn 6.5%, they could take out $66,795 per year. If they were in the 24% tax bracket, investing the $100k up front into a pre-tax plan would only have saved them $24,000 of taxes. But withdrawing $67k for 40 years ($2.7 million in total) would have cost them $641,231 of taxes. The more time you can grow the Roth, the less relevant higher taxes are to the cost/benefit equation. In the above scenario, the Roth might even win if future tax rates were lower than current.

Who should not convert.

Converting from pre-tax to a Roth is a strategy for many people, but not everyone. The most obvious obstacle is having money aside to pay the taxes for the conversion.

The other factor is time. You must give a Roth strategy a minimum of 5 years to be tax-free and I prefer to see a full decade of growth. If your timetable to spend from the account is less than a decade, then converting probably isn’t for you.

Converting to a Roth might also not be worth it if your income is in the lowest bracket and would remain among the lowest brackets throughout life.

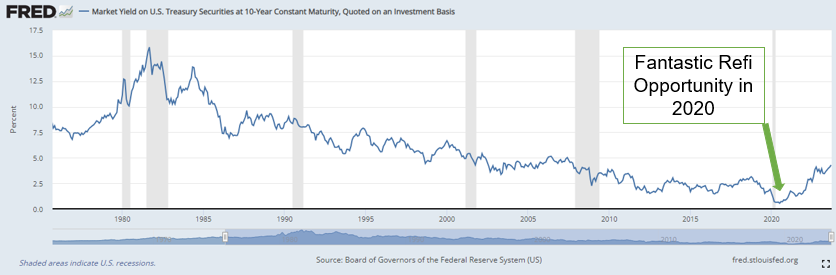

Another way to look at it

During Covid, the Treasury 10-year bond hit its lowest rate in its history at 0.32%. This bond has typically been a decent indicator of mortgage rates. It didn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that if you had not refinanced to a lower yield in the past decade, this was the time to get it done. There was nowhere but up for the rates to go from there.

This opportunity was available for most people, but not everyone. Some had such a small mortgage, or not many years left to pay on it, that the cost of a refinance was counterproductive to the savings of a lower yield.

However, for everyone else, it was one of the most obvious financial moves to make. Fast forward to today, when the 10-year bond has risen to 4.314% (an increase of 1,248%) and mortgage rates are significantly higher – those that refinanced have saved themselves potentially decades of higher expenses in mortgage interest. Especially if this is their final lifetime mortgage.

That is the same way that I view Roths today. Tax rates are the lowest they’ve been since the Great Depression, and especially since Covid, we have the worst fiscal balance sheet in the history of our country. Where do you think tax rates have to go from here? Up or down?

Let’s have a conversation if you are considering using Roths and especially converting. We want to be sure to understand what the tax ramifications will be and determine your cost/benefit.

James Studinger

Securities offered through Kestra Investment Services, LLC (Kestra IS), member FINRA/SIPC. Investment advisory services offered through Kestra Advisory Services, LLC (Kestra AS), an affiliate of Kestra IS. JP Studinger Group, LLC is not affiliated with Kestra IS or Kestra AS. Investor Disclosures: https://www.kestrafinancial.com/disclosures

The opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and may not necessarily reflect those held by Kestra IS or Kestra AS. The material is for informational purposes only. It represents an assessment of the market environment at a specific point in time and is not intended to be a forecast of future events, or a guarantee of future results. It is not guaranteed by Kestra IS or Kestra AS for accuracy, does not purport to be complete and is not intended to be used as a primary basis for investment decisions. It should also not be construed as advice meeting the particular investment needs of any investor. Neither the information presented nor any opinion expressed constitutes a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security.